*Note* This is an old piece originally published on circusnow.com A: Can you explain a bit about your creation process? Smoke and Mirrors is very philosophical and I am curious to know if you start with an issue you wish to investigate and then create choreography that interacts with it, or do you start with choreography and then notice the philosophical issues that are already at play in your work? C: Both of those things, they kind of happen simultaneously, and we don’t very often work in one particular issue or concept. Like Smoke and Mirrors has a lot of different things going on, just as one example of our work. There are a lot of issues and concepts, like it’s not about capitalism. It’s not about these really particular things and it’s also about all of them. Often how we’ll work is we will start with an idea, and then through the process of workshopping it we ask, “how do we go through this really specific idea and broaden it to be more universal?” So although there is a political angle to Smoke and Mirrors it’s not about any one politic, no particular “we’re trying to tell you this,” but a broader sense of “what’s actually happening in the world now and how are people being affected by it?” A: Do you have any particular theories that you research or is your work based on things you come into contact with every day? C: I would say mostly the latter, where it’s like how are we affected by what’s happening all around us, and then when there are particular things, maybe not so much in Smoke and Mirrors, but within other work that I’ve done, when I get to a point where it’s like, “oh I actually want more information about what’s happening in a situation, like I want statistics, then I’ll go and research it, but for me it usually doesn’t start with, “I’m going to make a research project and then base my movement on the research,” its more like something coming from a place that is personal to me. A sense of realness is at the core of what I am wanting and what is inspiring to me, not trying to take a topic that is separate from my experiences as a human being. A: I guess I ask mostly because I think at one time I read that Smoke and Mirrors had to do with the idea of the “other,” and I’m not sure where I read that. C: These are two different shows. I made a solo show called The Other, that’s probably where that got mixed up. That was about different states of silence, different states of solitude, about queerness, about otherness. A: What struggles have you had translating some of those themes into movement? C: It doesn’t feel like a struggle to me. If I’m interested in making work about something it means that I am feeling it in some way. If I’m feeling it in some way the only thing that I really know how to do as a human being is move my body in order to filter all of these things. A: Do you think music is something you hear and then decide to create corresponding movement, or do you have movements and then find music that goes with it? C: I would say both of those things. Then again, I’m sort of answering all of your questions with, “it is all happening at the same time.” I spend a lot of time with music and a lot of time alone with music, going deep with music, really deep listening. So I’ve thought a lot about music and the role it plays in my work, as well as artistically what a really positive relationship with music is. As a performing artist, and this is a little off topic, but something that I think about a lot within circus and within dance is that what happens with the music is that the act becomes sort of like a back up dance for the music, where it’s just a response to the music. And it can be paired really well together, certainly, but then I’ve also thought a lot about, “okay, well is that actually my work? Is that my art?” When I have people coming up to me after they see something on the trapeze and they tell me all of these things, particular adjectives about what they felt, which are all of the same adjectives about how I felt when I listened to that song, it brings up this questions of, “is this actually a realness or are they responding to the song?” You can’t really separate them. Its almost like I’m representing that song, even though I don’t know the artist who made this song, they don’t know that I’m doing this dance to this song, I am responding to it. And that’s not a bad thing, but it’s something that has influenced a lot of the research that I’ll do movement-wise. How do we actually source music? How do we source movement from our own rhythms, from our own tempos, from our own ways of naturally moving? What is our way of moving? So I work with music a lot, obviously, I want to work with really beautiful music, but I would say that although it does really affect me, it’s rare that I find a piece of music and decide I need to make an act to this song. It’s more finding a piece of music that is really symbiotic with the research I’m already doing and pairing it that way. A: Do you think that idea is something Laura considered when she made the act in Stitch where she didn’t use any music at all, and all the noises were from her movement and her breathing? C: Totally, but that happened on accident. She was working with some different songs and wasn’t very pleased with any of them, and she was rehearsing in the theatre and I walked in and she didn’t have any music playing, because she was just practicing the moves. And I walked in and it was total silence, I mean silence is one of the loudest things ever right? Where it’s like there actually isn’t silence, there’s so many sounds always. A: Right, it was a very intense act. C: Totally, so I walked in at that moment and just stopped and watched her and it was like, “this is the act, this is the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen,” because we’re listening to her breath, we’re listening to the creaks of the building. Working in silence is no new idea, it can be really, really beautiful. So certainly that was thought of, but in that regard, that one happened by accident, which is generally how the best things happen. A: I wanted to talk about two specific themes I’ve noticed in your work, and I don’t know if they are things you do intentionally, or if they just occur. It goes along with the idea of the sounds of silence, or when you use nudity, or a lot of exposure on the characters part; is that meant to represent a sense of vulnerability? How do you see vulnerability in your work? C: It doesn’t feel like an external ingredient that I want to bring in; it feels like the basis. For me, I generally don’t want to watch anything unless there is some sense of vulnerability in it. That’s what draws me in, that’s what makes me feel connected to a performer, as well as what makes me feel like as a performer I’m giving something real. So, certainly nudity is very vulnerable, to be naked on a stage. In the Other, my solo show, I’m completely naked in both the beginning and the end. It’s about being totally stripped down, like “here it is, this is what’s happening.” I want everything to be vulnerable. I mean, I want things to be strong and I want them to be vulnerable, I want them to be all kinds of things. In the past two years I’ve really been obsessing over balancing tricks on the trapeze, and one of the things that I really love about that whole process is that it’s really fucking vulnerable. It is physically really vulnerable, and although there is technique to it, it’s really just you standing on a trapeze bar without any hands, balancing. And the movement that comes out of the organic nature of that, that’s everything that I want to watch. A: As an audience member I’ve always found that move to be one of the most anxiety inducing tricks I’ve seen. C: Right! So I feel like within the role of vulnerability, especially in circus, what a lot of people are taught is how to polish the vulnerability out of everything and how to make everything super pristine. I actually like to watch a little bit of a struggle; I want to watch that process. Not to say that there aren’t a lot of people working with high skill technique that is really fucking vulnerable and they are really polished at it, but it’s a different thing. I want to see the rawness. So that’s an interesting one, of actually looking at the technical aspects of trapeze for example. It’s one thing to present vulnerability; it’s one thing to gesture vulnerability; it’s one thing to display a vulnerable character; and then it’s another thing to really make something physically, emotionally, psychologically vulnerable. How do you get into that state? A: I’m curious about your characters, because you do have distinct characters, but they seem almost interchangeable sometimes, which ties into my next question about gender. When I watch the two of you, especially since you have similar body types, there are a lot of similarities, and it breaks down these gender barriers. How are your characters viewed through the idea of breaking down gender? C: Within character development, going back to drawing from our own experiences as human beings, the closer we can stay to a place of what is actually true for ourselves, the more developed and real those characters are. All of us have a million different characters inside of ourselves, it’s a basic rule of clowning, find the thing about yourself that is real and exacerbate it. And I think that can be done in multiple directions. Like the characters in Stitch were very real parts of ourselves, but exacerbated in a particular way. Same thing with Smoke and Mirrors, not to say either of us are business people, but definitely we are under the trap of capitalism, just as much as anybody else. Within gender, Smoke and Mirrors is an interesting one, especially in the finale where we’re both almost naked and we’re both in the ropes doing a duet. That really was this thing of, okay, were not available. I am a queer man, Laura is basically my wife, we’re not sexually involved with each other, but are still very romantic and have a lot of sweetness. It’s a very queer relationship in that way. The last thing that we want to be doing or perpetuating in our artwork is continuing to instill these gender dynamics. And although I am the base in the duo, and although I am flipping around the flexible girl, it’s also about restructuring so that you can’t really tell whose body parts are whose. So it’s more than “I feel like gender is like this really big topic that I’m interested in exploring,” its more of like, as a queer person how do I do this beautiful aerial act and not be perpetuating the thing that I don’t want to be seeing in circus, which is basically faggots and flexible girls pretending to be in love. A: That is something that drew me to your work, and though you say that you’re the base, I don’t see it that often. I think it is pretty interchangeable, especially when you do things that are synchronized and show that both the female and the male are capable of doing these same motions. You exhibit flexibility too, so it’s not just the standard dynamic of very buff, strong male and then flexible woman being flown. C: No, it’s not that at all. And that’s really important to us, and even if it wasn’t important to us, like, I’m not a beefcake, you know what I mean? I’m strong, but I’m not that guy. So I think it’s really just encouraging what’s already happening, where it’s like how do we show the sweetness of our relationship, as well as be careful not have it become sexual? This is not the man and wife love duet. This is two humans who are having an intimate experience together, and how do we non-sexualize it? How do we use nudity and make it non-sexual? That’s another big one. How do we take off the clothes and have it be the most un-sexual thing? At least to us. So it’s interesting, I feel like people are way sexier, and there’s a lot more connotation, when clothing is actually involved, because of the presentation of clothing, and the presentation of gender through clothing. Take the presentation away and just have two bodies doing stuff, and it’s worked for us. A: What is your background? Do you come from more of a dance background? Does theatre have any influence on the work that you do? C: I think I’ve been to like four dance classes in my entire life, so that is not a part of my training. Really my dance background is, which sounds like such a joke to say this and is actually not a joke at all, I have an older sister who started bringing me into the psychedelic, electronic dance scene in the early 90s when I was eleven years old. And I sort of grew up in the rave scene in the 90s, and although there is this party component of that, what was happening culturally in New Mexico is that all of these things were out of doors, with really exquisite music, and really phenomenal, life changing moments were happening, which is where I learned about moving my body, and where I learned about energetics, and where I learned about the manipulation of energy. Though it sounds like a joke, I don’t want to discredit the fact that I was a raver for a decade, and really did a lot of movement research with psychedelics and dancing for hours and hours. So I feel like that is what sparked my interest, and then from that I got into yoga at the age of fourteen, and then that led into martial art training, then that led into more interest in acrobatics, and acrobatics led into finding a trapeze class. But it was all very self-directed. I never really had one particular teacher in anything. And I spent a lot of time alone in this theatre where we make all our work. I lived there for many years. I spent a lot of time alone up there just feeling the weight of the world and how it affected my movement as well as just obsessing, making things up. A: Have you ever had issues with the perception of your work? Has anyone ever come up to you and told you something about the work that you didn’t expect? C: A little bit. Mostly people are right with us. We have had some funny things, like we had somebody call Smoke and Mirrors “the marriage show” because they couldn’t remember the name. And we were sort of like, “what the fuck are you talking about?” And okay, there was no harm in it, but there are certain comments like that. But, for the most part people are pretty with us, and with us doesn’t mean you just get the thing, or maybe you get the broader thing and we were able to invite you into the state that we were interested in sharing with you, more than just the concept. I want people to feel connected, and I feel like we get that.

4 Comments

"A trivial problem reveals the limits of technology" had caught my eye, but not enough of my attention to get me to read more at the time I received the email. In my boredom I finally opened the article and was immediately drawn into the action filled drama that is the world of copiers, xerography, and tribology (don't worry, those words will mean more to you when you read the article, and you should).

The article read like the script for an action movie. Full of obstacles to conquer, fascinating sci-fi-esque technology, characters I felt invested in, and a lasting struggle. The article opens with the initial conflict that draws us into the story. Xerox engineers are faced with a problem: a paper jam had occurred in Asia while a client had been trying to print a book. With overwhelming enthusiasm I started reading quotes aloud to Esther. "The paper they had fed into the press was unusually thin and light, of the sort found in a phone book or a Bible. This had not gone well. Midway through the printing process, the paper was supposed to cross a gap; flung from the top of a rotating belt, it needed to soar through space until it could be sucked upward by a vacuum pump onto another belt, which was positioned upside down. Unfortunately, the press was in a hot and humid place, and the paper, normally lissome, had become listless. At the apex of its trajectory, at the moment when it was supposed to connect with the conveyor belt, its back corners drooped. They dragged on the platform below, and, like a trapeze flier missing a catch, the paper sank downward. " How, I asked Esther, was an article on copiers written with such literary mastery? We came to the conclusion the New Yorker had handed out a handful of topics to write on. The author, Joshua Rothman, had drawn the short straw and ended up with copy machines. Instead of being disappointed by his banal assignment he decided, "Oh yeah? Well I'm going to write the best article ever written about copy machines!" And he did. After our opening scene where we meet the engineers who are facing the problem of the lissome paper, Rothman takes us back in time, through the history that has led us to the modern copy machine. It all starts back in 1440 when Guttenberg invented the printing press. Though some advancements are made in the centuries between, the paper jam doesn't emerge in the replication process until the 1960s. This is because it takes up until this time to introduce multiple sheet printing. In 1938 a huge advancement in copying take place. In this year Xerography is invented, which is the process of using static electricity quickly and precisely to manipulate electrostatically sensitive powdered ink, a.k.a. toner. (That's right, you wondered what the hell toner was and why your copier keeps telling you it need it? Well, there you go.) With the invention of Xerography, copiers are faster and able to process sheet after sheet of paper, but it is the convenience of this rapid process that has led to the global frustration of the paper jam. Though every year technology improves in exponential jumps, for some baffling reason paper jams never seem to disappear. "There are many loose ends in high-tech life. Like unbreachable blister packs or awkward sticky tape, paper jams suggest that imperfection will persist, despite our best efforts. They’re also a quintessential modern problem—a trivial consequence of an otherwise efficient technology that’s been made monumentally annoying by the scale on which that technology has been adopted. Every year, printers get faster, smarter, and cheaper. All the same, jams endure." The problem lies in the fact that though the modern copy machine is an incredibly precise machine, the paper used is still natural, coming from the pulp produced from trees. "'Paper isn’t manufactured—it’s processed,' Warner said, as we ambled among the copiers in a vast Xerox showroom with Ruiz and a few other engineers. 'It comes from living things—trees—which are unique, just like people are unique.' In Spain, paper is made from eucalyptus; in Kentucky, from Southern pine; in the Northwest, from Douglas fir. To transform these trees into copy paper, you must first turn them into wood chips, which are then mashed into pulp. The pulp is bleached, and run through screens and chemical processes that remove biological gunk until only water and wood fibre remain. In building-size paper mills, the fibre is sprayed onto rollers turning thirty-five miles per hour, which press it into fat cylinders of paper forty reams wide. It doesn’t take much to reverse this process. When paper gets too wet, it liquefies; when it gets too dry, it crumbles to dust." It is these natural fibers that put unseen variables into the equation. Engineers have to focus not only on the machines they are fixing and creating, but they also must visit paper mills worldwide in order to make advancements in paper technology. But just like anything coming from the natural world, it seems impossible to completely weed out the discrepancies. Rothman leads us through this unseen world. Copiers play a monumental though subtle role in our lives (just wait till you get to the part about Chicago crime rates) and the problem of the paper jam is a metaphor for the "elemental battle between the natural and the mechanical." Technology inexorably continues to advance, but it seems that perhaps there will always be hangups, that natural taking its unexplainable and random revenge on the mechanical. In true literary fashion, Rothman takes us on this long journey only to drop us back off at the beginning, with the engineers staring at computer diagrams of the paper jam in Asia. Rothman asks a handful of the Xerox employees if they think the problem of the paper jam will ever be eradicated. Most seem skeptical. They turn their minds back to the task at hand, as long as paper jams persist they will have problems to solve--their elemental battle continues. Read the full article from the New Yorker here. Now that I'm not in Paris I don't have as much access to amazing performances, but I still would like to keep up with the writing I've been working on. I've spent the past two years as an art creator, making new performances and taking them all over the country. Now I'm taking a little break from being a creator to be a consumer of art. And I suppose one of the important things about being a consumer is to not just react to something on a surface level, but to be critical and thoughtful toward it too. So upcoming will be thoughts and critiques on the many things I've been coming into contact with, and how I compose those thoughts into something resembling a coherent analysis. A coworker and I spend a lot of time on the line at work sharing new music we've encountered. We've been talking about the incredible music coming out of Philadelphia right now and he introduced me to this band that has now been accompanying me on all my walks through town for the past week. Painted Shut is a graceful and poetic existential crisis. Powerfully sung by Frances Quinlan, Painted Shut is the third studio album from Philadelphia based band Hop Along. The album is a collection of directly or obliquely personal stories, allegorical references, and homages to forgotten music legends. It questions the legacies we leave and how we will be remembered, or just as likely, forgotten. The songs are preoccupied with how we are viewed through the eyes of others. Quinlan's voice is the sonic representation of this inner struggle. Often her voice becomes unrestrained and her calm, melodious singing breaks into that beautifully desperate and vulnerable scream. It shatters your heart and your resolve every time.

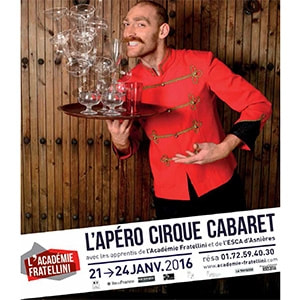

Two biographical songs, Buddy in the Parade and Horseshoe Crabs tell the stories of musicians Charles "Buddy" Bolden and Jackson C. Frank respectively. Both musicians were considered influential, but eventually suffered breakdowns and a loss of confidence and passed into obscurity. The forgotten haunt this album: an unmarked grave in Happy to See Me, an old man in Sister Cities hiding behind red flowers and a painted shut window, a West Virginia waitress in I Saw My Twin who is left behind as the band moves on to its next tour location. Quinlan laments the connections that were never made, how its our own fear and indifference toward forging bonds with the outliers that cause these people to disappear. In contrast to Quinlan's sadness for the forgotten is her fear of being remembered infamously. Guilt and shame over inaction permeate many of the songs. In Powerful Man the teenage Quinlan does nothing as a father abuses his son for looking at her and in Sister Cities the "false friend" keeps his back turned as the protagonist of the song learns "the fierceness of man / Again, again, again!" In the song Waitress Quinlan sings from the perspective of a waitress who is connected to one of her customers through a shared relationship. The other partner comes into the restaurant to be served and the waitress worries, "She must've known who I was / the worst possible version of what I had done." The waitress knows this woman will only recognize her for her weaker and more shameful moments and this causes her to fear how this other woman judges her, but just as quickly she rationalizes her actions through the same assumptions made in so many of the other songs; is she really important enough to be remembered? Because "by the time it's old / a face will have been seen / one and a half million times / ...and I'll share a very common poverty." The poverty of being forgotten, because as she sings in Buddy in the Parade, "Fool, all you touch on this turning dream / is either gonna be burned or buried." Just as many of the characters turn their backs on the suffering of others, Quinlan also turns her back on religion, but questions this choice. She is annoyed by having her morning coffee disturbed by Jehovah's Witnesses in the song The Knock, but by the end of the song she notices, "did you see the look on the face of the kid he brought with him? / I never once seen a teenager look so radiant." She is moved to tears by the calm and self-assuredness brought to this teenager through his religion and questions why she didn't talk to them. The other character in the song however questions her sentimentality, telling her "everyone is suffering." Quinlan shys away from religion again in I Saw My Twin when she sees a nun eating in a West Virginia Waffle House. Her ambivalence toward religion leads her to call the nun "a great black hole of providence," but as an afterthought she still asks someone to "please take pity upon the heart that lives in me." She is turning away from a religious answer to all her questioning, but she still hopes some sort of providence will intervene to give her clarity. The song that ties this whole album together, and perhaps answers all of Quinlan's questions for itself is Happy to See Me. In this song the narrator battles with trying to change her mind on how she views situations in her life, because just like the danger of "a defeated army headed home," if her feelings remain bitter and defeated she will only leave destruction in her wake. There are times though when the memories get the best of her and "tumble from the bridge / up and into the dark / thought up by a mind that must have been / a sort of sinister question mark." The song leaves us with the narrator on a train, hoping that in the end whenever she sees people from her past they will be happy to see her. She hopes that just as she is trying to do, people can be strong enough to allow their love to outweigh all the painful memories that cause them to trip upon their moralities. Just like the YouTubing father in the middle of this song, she is also saying, "People of the world, nobody loves you / half as much as I / half as much as I am trying to." Maybe she hasn't quite succeeded in working it all out, but the point is she is trying, because in the end we all end up shouting into whatever void will carry our desperate thoughts, hoping maybe someone will remember us fondly, if for nothing else, at least for how hard we tried.  A stylistic connection was obvious between Circus Remix and Grande (the first show I reviewed in this blog). Both shows were divided into multiple sections, had a strong focus on individual stunning tricks, and utilized inventive wordplay. And this would make sense considering the creators of these shows at one point had a company together called Ivan Mosjoukine. Though the members of this company now perform separate shows, their creative origins are still fully apparent in their new work. Maroussia Diaz Verbèke, the creator of Circus Remix, takes the wordplay a step further though. She has created her own term, "Circographe," to define her role in the circus. Related to dramaturgy, though not entirely similar, circographie is the creation of text that is specific to circus. This use of text was ubiquitous in the show, from the opening scene where Verbèke holds a series of signs explaining she will use words and movement to share her inner thoughts with the audience to the nearly nonstop projections of stream of consciousness writing. The projected words were accompanied by their verbal recitation, a jumble of sentence fragments Verbèke had collected from numerous interviews and pieced together to explain her own thoughts during the show. The show had many moments of stunning acrobatics, most notable a walk on the ceiling, dangling upside down by her feet as she crossed a horizontal ladder. There were also many moments of failure and accepting the limits of human physicality. At one point Verbèke circled the room showing off an antique circus poster of a woman diving from a high board to land in a handstand on a chair below. The spectators groaned and covered their eyes. After already witnessing several daredevil acts that seemed impossible, this seemed like her insane denouement. But it wasn't. Verbèke laughed, tossed the poster to the side, and moved on to the next, more subdued, part of the show.  One of the reasons I appreciate French contemporary circus so deeply is that they are able to tell an incredibly evocative story through simple means. The Académie Fratellini's Apéro Cirque series is a reoccurring event to present work from the school's apprentice program. Held in the school's smaller chapieteau with a three-quarter round stage and no set, the third year apprentices shared the story of a young boy named Mehdi. Mehdi likes to wear lipstick, and throughout the show he battles with his own confusion of identity as well as ostracism by his peers. Solo acts evoked various childhood emotions, while ensemble pieces showed the challenge of interacting with one's peers when not conforming to the normal social expectations. The poetic nature of the text was reflected in the apprentices' movements, from the opening scene of Mehdi's birth to the final scene in which each apprentice carried a piece of a Mehdi puppet-- holding an item of clothing that when put together showed the fragments that compose a young child, but not the child who occupied them. The audience is left with a final image of the tactile objects we use to represent identity, but they are hollow constructions, Mehdi's true image is left to our imagination.  L'Atelier du Plateau reminded me of the original Cirque Lab in Bellingham, Washington. It has a small floor plan, but high ceilings and an industrial look. The layout was more laid back than many of the professional venues I have been to in Paris, with as many folding chairs as possible crammed into the tight space, surrounding an open piece of the floor that became the stage. The performance was a variety show with themes that seemed to tie the acts together (though again my comprehension of the spoken parts may have been a bit weak). Several acts started with performers coming from the audience, acting as if they were mere spectators interacting with the performance. There were many moments of physical or social awkwardness that would be transformed into virtuosity by the performers interaction with their chosen apparatus. This was the 16th edition of the "fait son cirque" series, a collaboration between circus performers and musicians. Each night of the run different performers create an entirely new show, linking their acts with rotating live musical accompaniment. If the last few shows I attended were independent films at a local theatre, Cirkopolis was like seeing a Hollywood blockbuster at a Cineplex. Loosely based on Fritz Lang's Metropolis, a cast of multidisciplinary circus artists use acrobatics to rebel against the monotony of corporate life. The show is, at times, overstimulating with its pop music soundtrack and backdrop of cityscape projections. Overall the performance reminded me of Jaques Tati's film Playtime. There was a frenetic atmosphere with characters who spoke a jumbled and rapid mix of different languages and gibberish. The group numbers and comic pieces were engaging and expressed a contagious feeling of playfulness, but the serious portions seemed to lack the emotional relevancy they were searching for.  My favorite portion was when one of the clown characters tried to impress a woman who was made from empty clothing and a clothes hanger. Perhaps I'm slightly biased because he managed to find a clothing rack that was far more stable than the one I used in my own show, so he was able to use it as an apparatus to much greater effect. Personal jealousy aside, his character made me laugh out loud and provided an excellent transition into the following trapeze act. I always admire the ideas coming from the big circus companies in Montréal and their skills are at an unarguably high level, but often the final product seems slightly unoriginal and contrived. To refer back to the metaphor I opened with, these shows are fun and inspiring on a technical level, but rarely leave me with a deeper sense of meaning. The setting for this show was a web of tight wires at various heights. Platforms just big enough for a foot connected each wire. One man opened the show with a monologue, telling the story of his twenty years as a wire walker, a career that ended after a fall at the beach left much of his body paralyzed. Though not directly stated, the performance seemed to be memories from his life before his fall--his growth as an artist, his successes and failures on the wire.

Seven performers blended dynamic and often anxiety inducing tricks with character interactions that ranged from romantic to playful to competitive. A live band heightened the action and anxiety with well timed musical accompaniment. Discordant sounds built tension as performers prepared themselves for spectacular tricks such as backhandsprings or backtucks on the springy wire. Though the show was full of technically skilled physical performance, close attention was paid to the narrative arc. The show had several phases, starting with a curious and playful beginning and transitioning to the struggle of acquiring new skills and relationships. Later it moved to choreography that seemed to be an allusion to Pina Bausch's, with a solo performer awkwardly moving along the lines, slamming her body into other wires, like the repeated movements in Café Müller. The performance ended with one woman on the wire and the paralyzed man standing below. In synchrony they walked along their individual lines, the woman on the physical wire, and the man on its shadow below. This is the first performance I've attended since returning to Paris, and it helped me remember why I keep coming back to this city for artistic inspiration. I was told this was a show I had to see because though it was categorized at circus/music/theatre, it truly created a genre of its own. Blending live music, circus stunts, humor, and poignancy, two performers, Tsirihaka Harrivel and Vimala Pons, share small reviews of individual moments. Though there was a reasonable amount of speaking in the performance (and my French still needs some work), I was thoroughly entertained and able to follow the general themes.

Arranged on a series of tables is a mess of objects. Through the performers' interactions with these objects the importance of their seemingly innocuous nature is brought to light. A cross becomes a sword, a door a view screen, and a shelter a coffin. Harrivel and Pons create live music on an elaborate set of instruments, utilizing delayed sounds and repetitions. The music runs parallel to many of the repeated circus acts, though just like the music each of these repetitions have slight alterations. The performers' chosen circus acts are symbolic of aspects of each character's personality. Pons is constantly weighed down by alternating objects, from a life-size mannequin to a washing machine, while Harrivel is repeatedly lifted by each object he holds, attached to an electronic crane, to be dropped again and again down an eight meter chute. Grande juxtaposes banality and brutality, tenderness and violence. It can best be summed up by a line in its synopsis: "it resembles a juke box distributing poems."  Sorting through the tour vehicle Sorting through the tour vehicle It starts with emails. A lot of emails. First I e-mailed all the friends I had in various circus communities around the U.S. asking if they knew of appropriate performance spaces. The problem with finding a venue for a circus show is not only do you need high ceilings, but you need rigging from that ceiling that can bear a substantial amount of weight. Asking for 18-25 ft. ceilings is one thing, but finding safe and reliable rigging can be questionable when dealing with theatres that aren’t familiar with the force weight created by aerial performance. First I checked with friends who were familiar with aerial rigging. I’ve traveled quite a bit for performances, as well as worked with the online network Circus Now. This has helped me build a large network of circus contacts across the United States. Unfortunately, many professional theatres are concerned about the liability risks inherent in circus arts, so more often I contacted circus schools or training spaces that were willing and able to turn their space into a temporary venue. I gave them the pitch: I’m a circus artist with a thirty-minute solo show, which is admittedly a challenging length to book. However, I am traveling with a skilled emcee who has a wealth of material to help fill in extra time during the show. I’m also looking to share the stage with local performers. Part of the mission of this tour is to connect with other performers and circus communities, and it is my hope that I can offer spots in my show for performers of any skill level to present their work. My other expectation for this show is that it has donation-based ticket sales. This is a gamble when it comes to guaranteeing an income from the tour, but I strongly believe in making performance art accessible to people from all income brackets. In November of 2016 I began sending out my pitch to hundreds of friends, circus schools, training facilities, and theatres. Most didn’t even respond. Some wrote back to say they didn’t have enough resources to put on a show, or it was bad timing, or it just didn’t suit the mission of their particular space. But, a handful of emails came back intrigued by the show and the tour’s mission. Gradually I started piecing together cities and dates for a tour that would circle the U.S. from April to July, enough shows to have at least one performance a week for three months.  Performing at the Philadelphia School of Circus Arts Performing at the Philadelphia School of Circus Arts Once I had full tour lined up, it was time to create a budget and start fundraising. I bought a used 2004 Ford Ranger with a canopy and bed for sleeping, which would provide transportation from show to show and lodging while on the road. I estimated the cost of the tour would be anywhere from $6,000-$10,000, having the high end of the budget allow for the occasional hotel or catastrophic car failure. I started working six days a week to raise my own funds, and put up a campaign on Go Fund Me. I made an agreement with Anchorage Community Works, a non-profit art facility, to act as my fiscal sponsor so donations would be tax-deductible. In four months of saving I had enough in the bank to feel financially comfortable quitting my day jobs and leaving on tour. For the most part my tour budget was exceptionally low. I only allowed myself $70 a week for food, which meant buying groceries and cooking as much as possible. We basically lived off rice and vegetables (a mini portable rice cooker was a wise purchase). The lodging portion of my budget was also small. It allowed for the option of a hotel if we were absolutely in need, but it also made me search for cheap or free lodging. Many people associated with our venues opened their homes to us. Occasionally while on the road we would use free sites such as couchsurfing.com or freecampsites.net. The place I wasn’t frugal was with the transportation costs. I left myself a huge gas allowance and repair fund. I’ve had many friends who have had vehicles break down on tour, and I wanted to make sure we didn’t get stranded anywhere along the way. I was fortunate, the largest repair cost I had was $20 for a blown windshield wiper relay. At the end of March 2017, all the shows were set up, guest performers were arranged, and press packets were sent out. I met two members of my former circus troupe Capistrano Circus in Bellingham, Washington to start out the tour. Strangely, a Bellingham based cabaret performer and musician, would accompany me for the northern and east coast parts of the tour. Esther de Monteflores, a slack wire walker with her own solo show, would rejoin the tour in New Mexico. With the help of these artists and the guest performers in each city, we had a show that was long enough to fill an evening of entertainment. The most challenging part of tour was promotion. Finding ways to get people to show up when you are an out of town performer is difficult. I sent posters and handbills to each venue. I added my show to local events calendars and sent press releases to all the news sources I could find. In some cities I was able to get a slot on the local NPR station. Though theses tactics may have been helpful, I think the greatest asset to my audience numbers was the inclusion of local performers. It was an honor to present my work next to talented performers from all over the country, and having local names included in the promotion helped bring people to the shows. In the end the tour just barely broke even, and to me this was a huge success. A first tour is generally not a profitable endeavor, it’s about getting your name out in new locations. Often you spend more than you make. I was lucky, I had the opportunity to spend three months on the road, travel all around the country, and even occasionally pay my fellow performers, all for a final loss of around $300. Though it can be a disappointment to come home without a profit, sharing my work and meeting new circus communities was worth the small loss I incurred. I left Anchorage, Alaska with $2,000 in my checking account, and never had to transfer any money from savings. The amount of profit from each show was just enough to keep me on the road till the next. Theoretically I could have done this tour without saving money. The tour paid for itself. I wouldn’t advise hitting the road without any money in your savings account though. I was fortunate because this tour was free of problems. I didn’t have any serious car trouble and I was always able to find free places to stay. I took a few chances on expensive venues, and I was able to pay all those rental fees back with ticket sales. I would recommend at least a budget of $4,000-$5,000 to have peace of mind. I probably could have promoted more, but that would have cost more. The line between money spent on promotion and how many people it actually brings to your show is obscure. Though I didn’t make money, this tour was necessary to me because I practice contemporary circus, a genre that may be commonplace within the circus community, but is still relatively unknown outside of large cities. Many of the communities I visited had no idea what to expect from the show, but they came anyway to experience a new type of art. If I could change anything about this show I would try to book more shows in small towns. I was limited to the small towns I was already familiar with in order to find venues with safe rigging. The shows I booked in already established circus venues helped promote my work to the circus community, but my main goal was to push the knowledge of contemporary circus outside its isolated stronghold within the circus community. I hope my relative success on this tour will encourage others to take the final steps in booking their own tours. We are part of a small niche in the art world that is nurtured by performing within the safety of our own community. Contemporary circus will never be able to grow as an art form if more performers don’t take the risk of sharing their work with a larger audience.  Setting up at the Prop Box Setting up at the Prop Box The Venues The Cirque Lab I can’t be completely impartial when it comes to this venue, since it is the place I first started learning circus arts. The Bellingham Circus Guild is a charming community that has been growing over the past ten years to create an incredible space. The Cirque Lab has numerous rigging points, a large elevated stage and low overhead costs. They charge 20% of ticket sales, though this does not include a technician. The Cirque Lab does not require the use an in-house technician, so if you have the option of bringing a friend or technician along you can run your own tech. Bellingham is a small city that is supportive of the arts, so it is easy to promote a show through posters and local publications. Versatile Arts Versatile Arts does not frequently host shows and doesn’t have a dedicated stage, but if you are looking for an intimate performance space, this works to your advantage. The room has a large enough occupancy to become quite full, and it is easy to set up an in-the-round or three-quarter-round stage. Its other exceptional quality is you have plenty of height to work with, and pulley systems that make rigging quick and easy. Versatile Arts did require the use of their personal technician, but his prices were flexible. Versatile Arts is not generally a performance venue, but they appreciate promoting new performances and offer a reasonable ticket split agreement. Methow Valley Community Center I don’t think I can express enough how much I enjoyed working with this venue. Twisp, Washington is a small town with a population hovering around 1,000. For its small size, it hosts an amazing aerial coach and a talented group of pre-teen performers. We invited the girls to open the show, and were blown away by the level of skill coming out of this small community. The center itself is an old school house, which was a little tricky to set up as a circus venue. We weren’t able to use the stage because all the rigging points were in the center of the room. Once we set up some stage lighting though (rescued from the recently burnt down Twisp River Pub) the space looked a bit less like a gymnasium. They don’t have staff to run door or tech, so you will have to provide your own crew for this venue, but you will have complete artistic freedom with the space. Though this venue has a flat rental fee of $200-$300, you can almost guarantee a huge return. The town is small so it is easy to promote and you have very little competition. We set up about fifty chairs at the start of the performance, and as people continued to filter in we ended up rolling out the chair rack and had spectators grab their own chairs as they paid admission. This was by far the show with the highest profit and most engaged audience. The folks in this community are incredibly supportive of new art, and I hope those who read this will consider bringing more performance art to their town. Madison Circus Space For a small city in the Midwest, Madison has a very well established circus space. They don’t have a dedicated stage, but they have excellent stage lighting installed, so we were able to build our performance space based on the areas illuminated by the lighting. For this show I asked Sarah Muehlbauer, a performer I’ve known for ages but have never been able to collaborate with, to provide the opening material. Sarah bi-locates between Philadelphia and Madison, but I was able to catch her as she was putting together a new piece with a few Madison performers. The venue was wonderful to work with, though one of my more expensive financial agreements. You can choose either a flat rental rate or a 50% ticket split. For this tour, because my ticket sales were by donation, I always chose to go with a percentage split if that was possible. Fortunately, Madison has a strong social network of circus performers and enthusiasts. Most of our promotion didn’t extend past the local circus community, but we were able to fill the space through the social network and the popularity of the local performers. Esh Circus Arts Esh has a small occupancy of 40, but the tickets were sold out days before the show. The folks at Esh worked hard to ensure that we had an excellent line up of opening performers, including their visiting artists Terry Crane and Xochitl Sosa (which probably helped sell tickets so quickly). Their space is primarily a teaching facility, but they were able to create a beautiful stage by spreading out aerial silks for a backdrop. They also have custom-made scaffolding that extends throughout the building, providing ample choices for rigging. The Muse Brooklyn New York was the most challenging place I chose to book a show. Venue rentals are extremely high, and you are competing with a wealth of other choices for entertainment. When talking to the Muse I was apprehensive of the return this show would bring. The Muse does offer an excellent artist-in-residence option, which brings down the rental price significantly, but based on my budget still wasn’t low enough. They continued to help me out with options though, and eventually they found a local performer to pair me with who would help bring down the rental costs even more. Chriselle Tidrick is a local dancer who runs her own performance company, and she was invaluable in helping me navigate the complicated world of New York promotion. The venue has a large raised stage with several rigging points, and they are able to pull a curtain across half the room to make it seem more like a traditional black box theatre. However, it is still a very large space, and can seem quite cavernous to a small audience. This show was my largest financial risk, and I did end up having to pay some money for the venue, but based on the original cost of the venue I felt that it was reasonable. Depending on how much you want to present your show to a New York audience, you have to weigh the cost risks with the benefit that will come from exposure. Philadelphia School of Circus Arts We lucked out on timing with this venue. They don’t generally have a stage set up, but their student showcase was coming up, so they were already preparing their venue. Rigging is simple because the venue owns a Genie lift, so we didn’t have to lug a giant ladder around. We had a few lights on the floor that we had to run without a lighting board, which worked fine for my show, but could be challenging with more advanced technical needs. PSCA doesn’t do a lot of touring shows, so they didn’t have a dedicated tech person, but since the tech at this venue was so simple, we ran tech for each other without a problem. Unfortunately, we weren’t able to find many local performers for this show, but the staff promoted the show well through their social network and we had decent turnout. TheatreNOW This is one of the few professional venues I worked with that was not primarily circus oriented. I have had the opportunity to perform at this theatre several times while living in North Carolina, and they work hard to promote small budget events through their non-profit theatre program. The theatre also had open time during the week and I was able to teach a week long kid's circus workshop. The only problem with getting a discount on rental rates is you have to work around whatever dinner theater shows may be going on at the time. I chose a four day run of late shows (10 p.m.), with one earlier show on Sunday. This turned out to not be best timing. I’ve had better luck booking a single weekday show with an 8 p.m. slot. That said, even though the theatre is not built for circus, it happens to suit the form perfectly. There are only a few rigging points, but it is a lovely black box with 25 ft. ceilings. They also have great lighting and a skilled technician, making it an excellent venue to get high quality photos and video. Caroline Calouche & Co. This company started as a contemporary dance studio, but over the past ten years has expanded to incorporate aerial dance. At the time of my tour they had just completed their black box studio theatre. The stage itself was beautifully laid out, though the seating is somewhat limited. There are numerous rigging points and a large marley dance floor that allows easy transitions from aerial choreography to the ground. This is a great place to get footage of a show because the lighting and the curtains are set up to create a very professional looking setting. Wise Fool New Mexico One of my favorite things about working with Wise Fool is their commitment to socially relevant shows. I shared this performance with Esther de Monteflores, a former performer for Wise Fool’s show SeeSaw, and three local performers working on Devised Theatre pieces. The director of Wise Fool asked if Esther and I would be interested in performing our technical run-through for their teen summer program. She wanted to show the students an example of women who had created solo performances. Afterward we had a Q&A session with the girls to talk about the creation process for our two shows. This was a great opportunity to work with the community and inspire the next generation of circus performers. Wise Fool’s studio is cut in half by stage curtains, but since the space is mainly used as a teaching facility we had to hang up the back curtain before the show. Both aerial rigging and slack rope rigging were accessible on scaffolding. Wise Fool does not have a percentage split option for ticket sales, so I had to pay a $400 rental in advance plus tech fees. Though I had to pay for one technician, Wise Fool also had a handful of skilled volunteers to help with stage managing and ticket sales. I was a bit concerned about the rental costs, but we had a great crowd, many who came out to support the local performers. AirDance New Mexico AirDance Art Space is a gorgeous adobe church that has been repurposed as a circus specific black box theatre. They were able to accommodate slack rope rigging as well as aerial rigging. The lighting was somewhat limited with two light trees that weren’t attached to a light board, so we had to run the lights manually. We had planned a three day run in Albuquerque, which proved to be a bit unnecessary. One thing I learned about New Mexico is that people don’t seem to mind traveling between Albuquerque and Santa Fe, so with our show the week before in Santa Fe, one night in Albuquerque may have been a better choice. AirDance is a non-profit and had a flexible rental rate based on budget. They also provided lots of extra support through volunteers who were able to help with tech and door. The Prop Box This studio is a lovely practice space, occasionally turned venue, tucked away in the Bay Area. The best part about working with this venue was that they provided lodging, so I was able to have access to the space as long as it wasn’t being used for other rehearsals. The floor plan itself isn’t very large, and there is only one beam for rigging. The limited space however worked well for my show, which comes across better in an intimate setting where the aerial work is practically over the top of the audience. We set up a few chairs and mats for the audience, and once the room filled up it created a cozy, informal performance. Though I had performed my show in all types of venues, from highly professional theatres to cooperative art warehouses, this venue created the perfect setting for the final show of the tour. |

Archives

August 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed